Mussel culture basics (part 2)

In Mussel culture basics - part 1, I discussed mussel seed, both hatchery-purchased and in wild collection. There was also a chart with that column, which compared the steps in three mussel culture methods: bottom, single dropper socking, and continuous socking.

This column will explain socking, equipment, harvesting, and processing to complete the description of mussel culture basics.

Socking

Socking is not part of mussel growout if the bottom culture method is used. If longlines or rafts, either at the surface or submerged, are used as the culture method, however, growout is done in a socking material.

There are a number of different types of socking methods, each having potential depending on the region and specifics of the site. It's up to the grower to decide which to use.

In review there are two dissolvable type sockings, which have the special center core rope for strength. They are the Spanish style cotton / acetate wrap and the New Zealand cotton sock.

There are many styles of extruded plastic socking from several manufacturers throughout the world. They are inexpensive, but growers may find the material offers a limited mesh size selection, a variable stretch width, and, with some, limited strength.

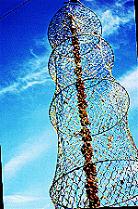

The Irish style of flat tape style socking with controlled stretch width and the newer knitted high strength socking that has controlled mesh size and stretch width, are options to consider.

Three factors regarding socking and output yields should be kept in mind:

1. Socking material strength has increased so as to allow longer droppers or to allow continuous socking deployment for higher yields per site;

2. Mesh size has a relationship to yield. To determine the right mesh size, the rule of thumb is that seed should need a gentle push to pass through the mesh-opening. This prevents premature drop off of seed that is smaller than the selected mesh.

3. Stocking density should be around 120 to 170 seed per foot, so set the sock's diameter accordingly. To do this effectively you must have a way of controlling the socking diameter. With an uncontrolled diameter, seed stocking densities can be as much as double the number of mussels finally harvested. That means half the seed planted was wasted due to drop off over the growout cycle.

Deploying socking

The following are some factors to aid in deploying and harvesting mussel socks:

Mussels in the water weigh approximately 25 percent of their above-water weight. Depending on the amount of bio fouling at your site, the in-the-water weight may become 35 to 40 percent. The weight factor could be as much as 50 percent when taking wave action into consideration. Therefore 200 pounds of mussels above water would be calculated as 100 pounds below water. Mussels have three dimensions: length, width (about 1/2 the length), and height (about 1/3 the length).

Socking is almost always done at a socking table using water as a flow medium, which enables the socking to be filled.

A table is normally a rectangular elevated box made from aluminum or plywood that has plastic or metal pipes protruding from the bottom corner. Socking is rolled over the outside on each pipe to a specific length. On demand, a valve is released and the seed mussels and water flow down the pipe into the socking.

A 6' sock can be filled in less than 30 seconds including the time to prepare the sock. The new high speed-socking table with 7' pipes can fill 450' of continuous socking in less than four minutes. While this is still not as fast as the continuous methods of New Zealand, which use a powered seed-socking machine, it is close and with lower upfront capital costs.

Depending on socking mesh size and growers' husbandry practices, socking deployment is either immediately or after an overnight soak in tanks to allow byssal thread attachment. This is especially true with larger mesh extruded plastic socks with ungraded seed. Once socks are deployed - either form surface or submerged longlines or rafts - the mussel will migrate to the outside of the socking where they will remain until final harvest. Or, in the case of the Spanish or New Zealand method, they will attach themselves to the center core rope while the socking material is dissolving.

The real trick here is to have the number of marketable mussels per foot be as close to the amount of seed deployed per foot as possible. It seems the average socking will yield up to 5 pounds of mussel per foot. With a size of 20-count per pound, that would mean 80 to 100 mussels per foot of socking. If the socking density were 120 to 170 seed per foot (see above), you can see that the seed conversion ratio is between 1.6 to 1.8:1. I have been on farms where conversion ratios are in excess of 4:1, which means that for every 400 seeds planted only 100 survived. The reason this is important, of course, is economics. Each mussel, once migrated to the outside of the sock, has to compete for space. If there is not enough, then it attaches to the next mussel, which has probably already attached itself to the other mussel, and so on. If the weight is more than the primary mussel's byssal thread can handle, the whole clump can fall off. This, combined with seed that fall out due to being mismatched with mesh size when initially socked, can cause extremely high seed conversion ratios. Growout times once socked can be anywhere from 12 to 28 months depending on initial seed size, site specifics, and region of growth.

Equipment

There are several factors such as wave action, wind, and ice to be considered in the deployment of longlines or rafts for mussel growout.

One problem to be aware of is predation, which primarily means ducks. Hungry ducks can be regional as well as site specific, and depending on migration habits, can include your farm on the availability of their food supply during their travels. The claim in the industry is that if you don't have a duck problem now, it may be only a matter of time before you do. While there have been a lot of attempts to ward off the ducks with numerous devices and physically activity, the most cost-effective protection seems to be rafts with predation nets around the perimeter. These are used on the West Coast of North America.

The other issues that need mentioning are starfish, bio fouling, sea squirt invasion, and theft control.

Since there is a good possibility that you will have a secondary set on your socking during the second year of your socking during the second year of your growout cycle, you will have to determine how to deal with it. According to current husbandry practices, methods for dealing with that set include a mid cycle harvest and redeployment; submerging the socking below the larval stratification level; or, depending on the size of the mussel, just ignore it until the final harvest. Those mussels can then be discarded or re-socked.

Almost all of the above challenges can be overcome with the submerged deep-water continuous longline technology that Dr. John Bonardelli has been working on in Eastern Canada. (For more information on Bonardelli's work see Shellfish Corner FFN Sept/Oct 1998.)

A number of different boat configurations are used in the industry, with catamarans, modified barges, and Cape Islander styles the most common. They can either be built as dedicated vessels or be modifications of existing boats.

For optimum use, boats should have a crane, powered star wheel, idler star wheel (longline), and hydraulic power. This is not to say that you couldn't make do with less; however the primary focus should be on safety. Once you decide on which husbandry method to use, plan from there.

Harvesting

Once mussels have made it through the final growout stage and are ready to be harvested, the socks are removed by hand from the longline, stripped by hand from the sock, machined, de-clumped, de-byssed, grade, and bagged ready for shipment to market.

In some areas like New Zealand, where growers are very mechanized, removal from the longline, de-clumping, and grading are done in one process. In some northern areas techniques for harvesting through the ice have been perfected so as to allow a year-round supply of quality product.

Right after spawning, mussel meat yields are very poor. As a result, harvesting is seldom done during that period due to the low product value and quality.

It is important to take into account such factors, though, when calculating inflows on your business plan.

Processing

The term primary processing is applied to the component of mussel production to make it ready to the live, fresh market. Secondary processing is applied to frozen, canned or cooked mussels.

Depending on the goals and focus of the growers, I have found that those who get involved in the promotion of their crops enjoy a much greater return for their product than those who don't.

It is important to remember that until somebody consumes what you grow, you are just spinning your wheels. As the production of cultured mussels continues to expand, consumption must increase also. Controlling quality is one key to that growth.

Mussel growers have a number of options for which to choose when deciding on socking material and methods. It's important to consider the region and specifics of the site when making the choice, with an eye toward achieving a profitable seed conversion ratio.

Contact Don Bishop at:

Fukui North America

110-B Bonnechere St.W.

Eganville, Ontario K0J 1T0

CANADA

**NEW**Fax: 613-432-9494

Email: don@bishopaquatic.com or don@bishopaquatic.com

Copyright © 1999-2004 Fukui North America. All rights reserved.